“Up, awake, ye defenders of Zion!

“Up, Awake, Ye Defenders of Zion,” Mormon hymn (c. 1848)

The foe’s at the door of your homes;

Let each heart be the heart of a lion,

Unyielding and proud as he roams.

Remember the trials of Missouri;

Forget not the courage of Nauvoo…

Tho, assisted by legions infernal,

The plundering foemen advance,

With a host from the regions eternal

We’ll scatter their troops at a glance

By His power is Zion surrounded;

Her warriors are noble and brave,

And their faith on Jehovah is founded,

Whose power is mighty to save.”

Framing

“Come, come, ye saints, no toil nor labor fear,” urges “perhaps the best-known and most beloved”[1] Mormon hymn, for “why should we think to earn a great reward / If we now shun the fight?”[2] Penned by LDS poet William Clayton, these compelling lines reflect the zeitgeist of the Mormon community in the wake of its violent expulsion from America and the harrowing pilgrimage across the plains to the new Zion in Utah (then within Mexico). The underlying ideology of the anthem is reminiscent of the crusade theology of Pope Innocent III as expressed in the quia maior, the call to the Fifth Crusade:

“So rouse yourselves, most beloved sons…gird yourselves for the service of the Crucified One, not hesitating to risk your possessions and your persons for him who laid down his life and shed his blood for you…sure that if you are truly penitent you will achieve eternal rest as a profit from this temporal labour.”[3]

Pope Innocent III, Quia Maior

The parallels between these two religious calls-to-action are clear. Both Innocent and Clayton implore listeners to plunge into a spiritual or literal fight, overcoming suffering for the sake of religious ideals. These texts are microcosms of broader patterns in crusades targeted against ‘heretical’ Christians.

My fundamental claim is that the rhetoric of both sides in the 1838 Mormon War exhibited the signature strategies of Innocent III’s ideology of anti-heretical crusade. In this context, ideology is the disparate set of “ideas, values, and accepted ‘truths’ of the culture that enabled – consciously and unconsciously – holy war.”[4] Ideology is the prism through which the culture views and interprets the world. Both the Albigensian Crusade and the 1838 Mormon War exhibit the same ideological elements despite being separated by six hundred years. I will demonstrate the resonance between these periods by uncovering common methods and worldviews in the primary sources, including: Innocent III’s quia maior and papal documents from the period of the Albigensian Crusade (1209 – 1229 AD), anti-Mormon rhetoric and Governor Bogg’s extermination order, sermons by key Mormon figure Sidney Rigdon and the founder Joseph Smith, and Mormon scripture in the Doctrine & Covenants.

These sources indicate common trends in the ways Christians portray and motivate action against rival movements within the faith. In other words, the significant actors in both periods wielded the same invisible weapons.[5] Using these weapons of ideas, Christians like Innocent III were able to manufacture consent for atrocity and bloodshed against fellow people of the faith. Together, these ideological tools compose an ideology of anti-heretical crusade: religious purification of the Christian community, the imitatio Christi, and the reclamation of the Christian inheritance – an actual Jerusalem or an imagined Zion.

Ideology of Innocent III

The central currents of the crusading ideology of Innocent III, arguably the most influential pope in history,[6] can be summarized in three words: purification, imitation, reclamation. Innocent unleashed a seismic ideological shift that turned the Crusades inward, against targets within Christendom. To accomplish this change, Innocent III forged an armory of rhetorical weapons and “progressively augmented the spiritual benefits to be gained by suppressing heresy.”[7] Papal documents of the early 13th century establish this trend.

Purification is rooting out toxic elements within the Christian community. The Albigensian Crusade and the Fourth Lateran Council were both components of Innocent’s endeavor to “purify Christian society at home.”[8] The zeal to eliminate the heathens partially arose from the same motivation for eradicating a virus: to prevent spread. Innocent warned a Provençal archbishop that the Cathars would “seduce the hearts of listeners” and lure them all into “pit of perdition together.”[9] In his letters he often used the imagery of infection, calling the enemy “pestilential,”[10] a disease that must be eliminated so that the “body of Christ may be built up until we all reach unity.”[11] Thus, Innocent called a crusade against the perceived blasphemous virus, and gave an ultimatum to the Langedouc heretics: renounce or perish.[12] His ideology portrayed purifying crusades as necessary to keep the Christian body intact and uncontaminated.

Imitation is the call to mimic the Messiah. Innocent used the ideological potency of this imitatio christi to instill in Christians a desire to suffer the Passion as crusaders. In the quia maior, Innocent declares the Fifth Crusade “on behalf of him who when dying cried with a loud voice on the cross,”[13] showing that the figurehead of Catholicism himself would also seek to imitate Christ. He likened the sacrifices of the crucesignati to the way the Son of God gave his blood and his life. Innocent even proclaims that true crusaders can be “equally certain” as Christ himself in receiving the ultimate reward — eternal salvation.[14] The final line declares that crusaders are “acting in the office of Christ’s legation.”[15] Comparison to Christ, the imagery of Jesus’ afflictions on the cross, and supplications to emulate and fight for the Messiah proved to be potent pieces of ideological equipment in justifying crusades.

Finally, reclamation is the attempt to recapture the sacred Christian inheritance of the Holy Land and Jerusalem. As Innocent sermonized: “snatch the land that Your only begotten son consecrated with his own blood from the hands of the enemy of the cross and restore it to Christian worship.”[16] Innocent decreed that Psalm 79 should be sung across Europe, echoing the drive to rescue the holy “inheritance” from the “heathens” in the name of the “only-begotten son.”[17] In this view, the Levant was rightful Christian soil, and the crusades were a matter of recovery, not conquest. Jerusalem was seen as the “navel of the world” by medieval Christians, who portrayed the land of Christ’s ministry as “fruitful above others, like another paradise of delights.”[18] Crusade was essential to save the sacrosanct and precious lands of Christ from defilement.

Parallels

The remainder of the paper will reveal the symmetries between Innocent’s anti-heretical crusading ideology and the rhetoric of the 1838 conflict. These similarities are revealed by comparing Innocent’s key papal bulls with the critical documents surrounding the 1838 Mormon War. In casualties, this war was somewhat insignificant: less than thirty individuals perished directly because of the conflict.[19] However, almost 175 years later, it is clear “the trauma of the Missouri experience dramatically shaped the development of Mormon theology, community, family, and ideology.”[20] The violence has an outsized impact on the Mormon historical memory.

Reclamation of Zion

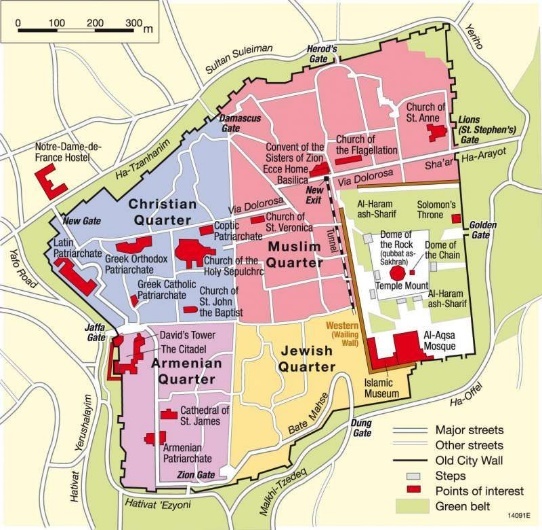

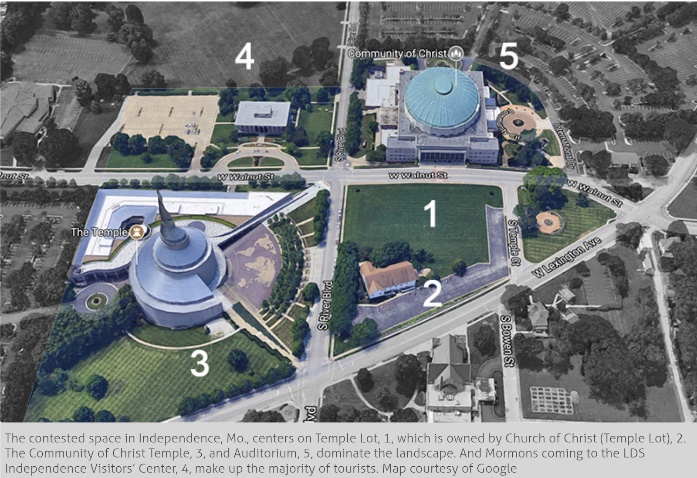

Both Catholic crusaders and Mormon pioneers sought to reclaim a lost promised land. The crusaders battled for the Holy Land in the Levant. The Mormons recognized the sanctity of the original Jerusalem, but they also struggled to find or build a New Jerusalem in America. In these efforts, Missouri is paramount as “the land which I [God] have appointed and consecrated for the gathering of the saints,” and because Independence is the “city of Zion.”[22] There is an entire sacred landscape based in Missouri. The state contains many of Mormonism’s hallowed sites, including Far West, “the spot where Cain killed Abel,”[23] the Kirtland Temple, the location of many of Joseph Smith’s prophetic visions and revelations,[24] and Adam-ondi-Ahman,[25] where Joseph believed Adam and Eve lived after their Fall from the Garden of Eden.[26] Just as the Abrahamic ‘people of the book’ try to share the holy sites of Jerusalem, three different Mormon denominations share the sacred land of Independence.[27] Thus, analogous to the recurring Catholic crusades to seize Jerusalem from the 11th to 15th centuries, the conflicts over Missouri in the 1830s held immense gravity for Mormons. The quest to control sacred soil was at the foreground of religious warfare both in Missouri and medieval Europe.

Preaching that “God would deliver Zion into the Saints’ hands by destroying the wicked,” some influential members of the LDS Church believed that a “Mormon takeover of Jackson County was preordained.”[28] Rumors of an impending conquest by an unfamiliar religious sect and “publicized declarations of divine entitlement to Missouri lands” spurred outrage and fear amongst the locals.[29] In response, anti-Mormon throngs brutally ejected the Mormons. Assembling an armed force called Zion’s Camp, some LDS leaders tried to retake the lost sacred land, but this expedition fizzled out without bloodshed.[30] Eventually, the church migrated to Far West.

However, the refugees faced similar problems in their new settlement. Some of their neighbors sent terrified letters to the governor claiming that the ‘fanatics’ were cooperating with “Indians of various tribes” to “work the general destruction of all that are not Mormons.”[31] Tensions soon surpassed a breaking point. Early Mormon authors wrote that a mob stormed into Far West in 1833 with a scarlet flag “in token of blood,” and announced that “the Mormons must leave the county en masse or that every man shall be put to death.”[32] The Mormons argued that their enemies used ideological weapons “to stir up the murky pool of popular prejudice to a crusade against a peaceable, prosperous, and law-abiding people.”[33] The reclamation rhetoric of the Mormons, and their imagination of a new Zion in Missouri, may have partially instigated a violent backlash. Ultimately, the Mormons were banished.

The tragedy of the loss of Zion is an immense legacy in the Mormon historical memory. Some contemporary Mormon sources referenced Psalm 79, the verses which served as the primary raw material in crafting Innocent’s crusade calls. One poet cited the Psalm in the first page of his poem lamenting the expulsion from Missouri: “Our eyes are dim, our hearts heavy / No place of refuge being left.”[34] This is also evocative of Innocent’s frequent references to Lamentations 5, which weeps that “our inheritance has been handed over to strangers…we have lost that land which the Lord consecrated.”[35] Many LDS hymns extol the effort to restore Zion or to establish a New Jerusalem.[36] As the verse on the front cover of this paper attests, Mormons cannot forget the trials of Missouri any more than medieval Christians could forget the 637 AD capture of Jerusalem.

The Mormons responded to the violence with a shift in ideology. The relentless reprisals against the faithful “spurred the radicalization of Mormon theology in the early 1840s.”[37] During the conflict, Joseph preached to troops assembled at Far West “that the kingdom of God should be set up, and should never fall,” declaring that “the Lord would send angels, who would fight for us; and that we should be victorious.”[38] After Rigdon argued that dissenting members of the Church should “be trodden under foot of men”[39] in his ‘Salt Sermon,’ some Mormons organized a vigilante militarist group called the Danites. The Danites believed they had a duty to take the land of Missouri, “that it was the will of God they should do so; and that the Lord would give them power to possess the kingdom.”[40] While they rarely engaged in actual conflict, this paramilitary group served as the ideological shock troops in the Mormon counter-crusade against the Missourians.

After all, according to doctrine, the Missourians were gentiles occupying territory divinely granted to “the remnant of Jacob” (e.g. Native Americans) and “heirs according to the covenant” (e.g. Mormons) as “the land of [their] inheritance.”[41] As official LDS scripture given by Joseph Smith in 1831 states: “ye shall assemble yourselves together to rejoice upon the land of Missouri, which is the land of your inheritance, which is now the land of your enemies.”[42] This is almost identical to the phraseology Innocent III repeatedly used to motivate crusading: from commanding Christians to “free…his inheritance from the hands of the Saracens”[43] in the post miserable of 1198 to his oft-cited Psalm 78: “the gentiles have invaded your inheritance.”[44] In both contexts, portraying the land as a religious heritage rather than mere conquerable territory was vital in motivating violent action to regain the venerated places.

Imitation

During the skirmishes of the 1830s, Mormon soldiers sometimes announced their arrival with the “trumpet tones [of] the old Jewish battle-cry, ‘The sword of the Lord and of Gideon.’”[45] This practice and many others underscore the ways the combatants of the Missouri conflict sought to imitate Christ, saints or historical Christians, and scriptural heroes. In this conflict, Smith unsheathed his rhetorical sword, and declared to his early disciples that “I will lead you to the battle.”[46] The imitatio Christi proved to be an essential element in encouraging the defense of Zion.

The language of crusade was quickly adopted in 1838 to instill a sense of the significance of the conflict and inspire analogies to Christ and the persecuted saints of history. W.W. Phelps, a writer of many key Mormon hymns, said at the time that “the crisis has come,” and that “nothing but the power of God can stop the mob in their Latter Day crusade against the church of Christ.”[47] After 1838, there was a “massive outpouring of writings and petitions describing the violence,” and Mormons argued that their oppressors were like “the tormentors of the ancient saints,” even “portraying Boggs as Nero.”[48] Sometimes, Mormon rhetoricians “used the memory of persecution to justify violence.”[49] These trends indicate the way Mormon figures drew continuities between their own situation and the situation of the Christlike saints and their enemies.

Crusader rhetoric was not just applied to vindicate Mormons, but to vilify their foes. In line with the Mormon belief, secular onlooker Thomas Kane sought to defend the Mormon’s image to counter the “‘Holy War’ waged against them by evangelical America.”[50] This rhetorical method proved invaluable. One LDS author satirized the anti-Mormon use of crusader rhetoric, saying that it was abundantly clear the Missouri militiamen were “worthy scions of the old [crusader] stock, and members of this honorable fraternity.”[51] The ironist describes how one Missourian “pursued them till the blood gushed from their feet,” “burning and destroying heretic’s houses,” and thus “redeemed himself in true evangelical style.”[52] This author’s use of ‘evangelical’ as an insult is remindful of the way Arab or Muslim sources use the term ‘crusader’ to impugn foreign invaders. Clearly, representations of holy warriors can be positive or negative, depending on if those depicted are allies to those doing the depicting.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/64559420/1690958.0.jpg)

Hymns are critical in ideological conflicts; a Mormon author wrote that a “hymnbook is as good an index to the brains and to the hearts of a people as the creed book.”[53] These invisible armaments often surpassed physical weapons in effectiveness. A medieval historian wrote that the enemies of the crusaders in the Languedoc “feared those who sang more than those who fought.”[54] Expressing similar sentiments to the Mormon hymn cited on the front page, the Catholic hymn Veni creator spiritus was widely adopted by crusaders during the Albigensian Crusade:

Far from us drive our deadly foe;

true peace unto us bring;

and through all perils lead us safe

beneath thy sacred wing.[55]

The Mormon lyricist also extolled his LDS audience to remember they were by “his power in Zion surrounded,” even as “legions infernal” and “plundering foemen” advanced against them. This example shows that both groups used the same lyrical methods to glorify spiritual or physical crusades and place them into a context of religious symbols. Especially impactful in both periods were the ideas, language, and emblems of the imitation of Christ.

Purification

Like the Catholicism of 13th-century Europe, the Protestantism of 19th-century America “required that communities be whole, an ideal that demanded the removal of social deviants.”[56] In the views of some, this merited the destruction of Mormonism and other aberrations. The drive to extinguish difference also reflects an underlying Christian persecuting society, which partly arose from the “fear of schism [that] had attended the church since its infancy.”[57] Like Innocent III, American preachers of the early 1800s also confronted an ever-splintering variety of divergent Christian movements. To contend effectively amongst religious discord, some revived the anti-heretical methods of the medieval enforcers of Christian orthodoxy.

Mormonism was not an isolated target of persecution. The attacks against Masons, Catholics, and Mormons, and Jews in the US at the dawn of the 19th century were manifestations of a “subsurface current of American thought” which at any time could “erupt in a geyser of hostility upon a tight-knit minority.”[58] These persecuting movements had a common base of support in “New England, the rural areas, and the Protestant ministers,” and “a great part of the propaganda against the Mormons was carried on through books and sermons of Protestant ministers.”[59] Anti-Mormonism was a wave in a larger tide.

These ministers also exploited the same rhetoric that Innocent III used so forcefully: the purification of the communal body. Their sermonizing expressed a “feeling that American purity was being contaminated by these alien groups,” especially with “such epithets as ‘stain’ or ‘cancer’ in the body politic, in reference to the Mormons,” in an attempt to persuade governments and individuals to “force Mormon conformity.”[60] The anti-Mormon ideological campaign proved successful in the end. In fall 1838, Missouri executive order #44 was issued. The orders from Governor Boggs stated “the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace.”[61] This constituted “no ordinary military directive, but a call for the eradication of a distinct people whose very existence could no longer be tolerated.”[62] Only rescinded in 1976,[63] the order reflects the intensity of the persecuting society on the American frontier and the vehemence of early anti-Mormonism.

The general of the Missouri state militia informed the Mormons that “you need not expect any mercy, but extermination, for I am determined the governor’s orders shall be executed.”[64] Furthermore, as the heretics were so frequently compared to an infectious virus, many officers involved in the expulsion thought the Mormons and all those close them to needed to be eradicated, root and stem. One Missouri cornel during the massacre of Haun’s Mill ordered his men to “kill and scalp all, little and big: nits make lice.”[65] This is a horrifying (but likely unintentional) emulation of papal legate Arnaud Amalric, who ordered during the sack of Béziers, “Kill them all. God will know his own.”[66] The ideology of purification is powerful and dangerous, encouraging atrocities during the anti-heretical crusades in both Languedoc and Missouri.

Conclusion

There is a fundamental similarity in the crusader rhetoric used during the expulsion of the Mormons from Missouri and during the inquisition against the Cathars in the Albigensian Crusade. The disparate threads of 1838 and 1213 are connected by a common tapestry of sectarian violence and persecution of heretics in Christianity, which is largely rooted in ideological shifts that took place in the early 13th century under the papacy of Innocent III. Ultimately, the rhetorical, ideological, and liturgical trends of anti-heretical crusade are visible in the historical moments of both 13th century crusading Catholicism and 19th century migrating Mormonism, and two distant historical moments use similar ideas and methods in their efforts to both promote and defend against anti-heretical crusade.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Bird, Jessalynn, Edward Peters, and James M. Powell, eds. Crusade and Christendom: annotated documents in translation from Innocent III to the fall of Acre, 1187-1291. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

“Bill of Damages, 4 June 1839.” The Joseph Smith Papers. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/bill-of-damages-4-june-1839/8.https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/bill-of-damages-4-june-1839/8. Accessed 4 Mar 2020.

Cater, Kate B (1969). Denominations that Base their Beliefs on the Teachings of Joseph Smith. Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Salt Lake City, Utah: Sawtooth Books, p. 50.

Clark V. Johnson, ed., Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833–1838 Missouri Conflict, (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 103–119.

Clayton, William (1814-1879). “Come, Come Ye Saints.” Manchester Hymnal, English. English. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1840. 1912, 25th Edition (last known). 385 songs. The lyrics were written in 1846.

Cordon, Alfred. “Times and Seasons, 16 May 1842, vol 3, no 14” p. 793, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed March 4, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/times-and-seasons-16-may-1842/11

Cordon, Alfred. “Times and Seasons, 16 May 1842, vol 3, no 14” p. 793, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed March 4, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/times-and-seasons-16-may-1842/11

Crosby, Fanny J. (1820-1915), “Behold! A Royal Army,” LDS Hymnal, #251.

Daniel Ashby, James Keyte, and Sterling Price (Brunswick, Missouri), “Letter to Governor Lilburn W. Boggs” (Jefferson City, Missouri), September 1, 1838, in Mormon War Papers 1837-41, Missouri State Archives.

Daniel Dunklin to “Dear Sir,” 1 June 1832, Daniel Dunklin Papers, 1815-1877, Western Historical Manuscript Collection, University of Missouri-Columbia

E. R. Snow, “The Ladies of Utah, to the Ladies of the United States Camp in a crusade against the ‘Mormons,’” Deseret News, October 14, 1857, 4, emphasis in the original.

E.R. Snow, “The Ladies of Utah,” Deseret News.

Genesis 35:2, The Bible, Genesis 35:2, The Bible, New International Version (NIV).

“History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834].” The Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834/481.https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834/481. Accessed 4 Mar 2020.

“Innocent III, Quia Maior, 1213.” In Crusade and Christendom: Annotated Documents in Translation from Innocent III to the Fall of Acre, 1187-1291, edited by Bird Jessalynn, Peters Edward, and Powell James M., 107-12. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

Innocent III, “29 May 1207: Innocent to Count Raymond VI of Toulouse,” Patrologiea Latinae, in “Appendix F: Translated Extracts from Papal Correspondence, 1207-1215,” HA, 304.

Innocent III, Ne jos ejus, 1208. Cited in Rist, Rebecca. “Salvation and the Albigensian Crusade: Pope Innocent III and the plenary indulgence.” Reading Medieval Studies 36 (2010): 95-112, pg. 100.

Innocent VIII (1669). Id nostril cordis. Histoire générale des Eglises Evangeliques des Vallées du Piemont ou Vaudoises. Pg. 8.

James 4:7-9. The Bible. Authorized (King James) Version (AKJV).

Jean Guiraud, St. Dominic (London: Duckworth, 1901), pg. 66. From the Papal Bull dated 19 April, 1213.

“Letter from William W. Phelps, 1 May 1834.” The Joseph Smith Papers. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-from-william-w-phelps-1-may-1834/1.https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-from-william-w-phelps-1-may-1834/1. Accessed 4 Mar 2020.

Matthew 21:10-17. The Bible. New International Version (NIV).

Matthew 5:13. The Bible. King James Version (KJV).

McGlynn, Sean. “The Song of the Cathar Wars: A History of the Albigensian Crusade by William of Tudela.” The Catholic Historical Review 83, no. 83, no. 2 (1997): 312-313.

Mills, William G. (1822-1895), “Come, All Ye Saints of Zion,” First LDS Hymnbook 1835, hymn number 40.

“Petition to Congress.” The Latter-day Saint’s Millennial Star, No. 28, vol XVII. Saturday, July 14, 1855. Reprinted from the History of Joseph Smith, a copy of the ‘petition to Congress for redress of our Missouri difficulties.’

“Polygamy and Utah,” The Latter-day Saint’s Millennial Star, No. 8, vol XVII. Saturday, February 24, 1855.

Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay. The History of the Albigensian Crusade. Edited and translated by W. A. Sibly and M. D. Sibly. Woodbridge, UK: 1998. §226.

Phelps, William (1792-1872), “Praise to the Man,” LDS Hymnal, #27.

Phelps, William W. (1792–1872).“Come, All Ye Saints of Zion.” First LDS Hymnbook 1835, #38.

Pope Innocent III. “Quia Maior.” Patrologia Latina. Ed. Migne, vol. 216.

Pratt, Orson. “Valley of God.” Journal of Discourses 18:343.

Scholz, B.W. (trans). Royal Frankish Annals. University of Michigan Press, 1970.

Smith, Joseph Fielding. Life of Joseph F. Smith. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1938. Pg. 340.

Smith, Joseph. History of the Church. Vol. 1.

The Doctrine and Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981. Section 57:1-2.

The Doctrine and Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981. Section 52:42.

The Ohio Republican. Zanesville, Ohio. Saturday, Aug. 24, 1833.

Turoldus, trans. Burgess, Glenn. The Song of Roland. London, England: Penguin The Song of Roland. London, England: Penguin Books, 1990.

W. G. Mills. “Song.” Deseret News. January 20, 1858.

William J. Purkis (2014). “Memories of the preaching for the Fifth Crusade in Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Dialogus miraculorum.” Journal of Medieval History, 40:3, 329-345. 329-345.

William of Puylaurens. The Chronicle of William of Puylaurens: the Albigensian Crusade and its Aftermath. Trans. W. A. Sibly and M. D. Sibly. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2003.

Wylie, James Aitken. The history of Protestantism. Vol. 2. Cassell Petter & Galpin, 1874. B. 16, ch. 1.

Secondary sources

Alexander, John Kimball. “Tarred and Feathered: Mormons, Memory, and Ritual Violence.” PhD diss., Department of History, University of Utah, 2012.

“Adam-Ondi-Ahman.” Emp.Byui.Edu, 2020. http://emp.byui.edu/SATTERFIELDB/PDF/Quotes/Adam-ondi-Ahman.pdf. http://emp.byui.edu/SATTERFIELDB/PDF/Quotes/Adam-ondi-Ahman.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar 2020.

Bauer, John W. “Conflict and Conscience: Ideological War and the Albigensian Crusade.” Masters thesis, United States Military Academy, West Point, New York. 2007.

Baugh, Alexander L. “A call to arms: the 1838 Mormon defense of Northern Missouri.” PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1996.

Bell, Angela. “Trouble in Zion: the radicalization of Mormon theology, 1831-1839.” PhD diss., University of Missouri–Columbia, 2017.

Brandon G. Kinney. The Mormon War: Zion and the Missouri Extermination Order of 1838. Yardley, Penn.: Westholme Publishing, 2011.

Brown, Samuel Morris. In Heaven as It Is on Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Cannon, Mark W. “The crusades against the Masons, Catholics, and Mormons: Separate waves of a common current.” Brigham Young University Studies 3, no. 3, no. 2 (1961): 23-40.

Cohen, Charles L. “In Heaven as It Is on Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death.” (2016): 170-173. Pg. 290.

Crandall, Marilyn J. “The Little and Gardner Hymnal, 1844: A Study of Its Origin and Contribution to the LDS Musical Canon.” Byu Studies, vol. 44, no. 3, 2005, pp. 136–160.

Crawley, Peter, and Richard L. Anderson. “The Political and Social Realities of Zion’s Camp.” Brigham Young University Studies 14, no. 14, no. 4 (1974): 406-420.

Elaine Pagels. Beyond Belief: the Secret Gospel of Thomas. New York: Random House, 2003.

Frampton, T. Ward. “’Some Savage Tribe’: Race, Legal Violence, and the Mormon War of 1838.” Journal of Mormon History 40, no. 40, no. 1 (2014): 175-207.

Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia. “RESEARCH PROPOSAL: CRUSADE, LITURGY, IDEOLOGY, AND DEVOTION (1095-1400).” Neh.gov, Research Grant FB-56015-12.

Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia. Invisible weapons: liturgy and the making of crusade ideology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Gaskill, Alonzo L. (2013), “Michael G. Reed’s Banishing the Cross: The Emergence of a Mormon Taboo [Book Review],” BYU Studies Quarterly, 52 (4): 185.

Givens, Terryl. The viper on the hearth: Mormons, myths, and the construction of heresy. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Gordon S. Wood, “Evangelical America and Early Mormonism,” New York History 61 (October 1980).

Grow, Matthew J. “The Whore of Babylon and the Abomination of Abominations: Nineteenth-Century Catholic and Mormon Mutual Perceptions and Religious Identity.” Church History 73, no. Church History 73, no. 1 (2004): 139–67.

Grow, Matthew J.. “The Suffering Saints: Thomas L. Kane, Democratic Reform, and the Mormon Question in Antebellum America.” Journal of the Early Republic 29 (2009): 681 – 710.

Grow, Matthew J.. “The Suffering Saints: Thomas L. Kane, Democratic Reform, and the Mormon Question in Antebellum America.” Journal of the Early Republic 29 (2009): 681 – 710.

Grua, David W., “Memoirs of the Persecuted: Persecution, Memory, and the West as a Mormon Refuge” (2008). Theses and Dissertations, Brigham Young University.

Hartley, William G. “Missouri’s 1838 Extermination Order and the Mormons’ Forced Removal to Illinois.” Mormon Historical Studies 2, no. Mormon Historical Studies 2, no. 1 (2001): 5-27.

Hertzberg, Benjamin R. “Just War and Mormon Ethics.” Mormon Studies Review 1 (2014): 144-154.

Hertzberg, Benjamin R. “Just War and Mormon Ethics.” Mormon Studies Review 1 (2014): 144-154.

Hicks, Michael. Mormonism and music: A history. Vol. 489. University of Illinois Press, 2003. Pg. 20, quoting Alexander Campbell.

Howlett, David J. Kirtland temple: The biography of a shared Mormon sacred space. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Largey, Zachary L. “The Rhetoric of Persecution: Mormon Crisis Rhetoric from 1838-1871.” (2006). Theses and Dissertations, Brigham Young University. Pg. 67.

Moore, John, ed. Pope Innocent III and his world. Routledge, 2016.

Moore, Robert I. Moore, Robert I. The formation of a persecuting society: authority and deviance in Western Europe 950-1250. John Wiley & Sons, 2008. Pg.

“Mapping the Global Muslim Population.” 2009. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. https://www.pewforum.org/2009/10/07/mapping-the-global-muslim-population/.https://www.pewforum.org/2009/10/07/mapping-the-global-muslim-population/. Accessed 7 Mar 2020.

Nickerson, Hoffman. The Inquisition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1923. Pg. 35.

Nunn, Alexis, “The Albigensian Crusade: The Intersection of Religious and Political Authority in Languedoc (1209-1218)” (2017). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 57. Pg. 1.

O’Carroll, Michael. Veni Creator Spiritus: A Theological Encyclopedia of the Holy Spirit. Liturgical Press, 1990. Pg. 65.

Power, Daniel. “Who went on the Albigensian Crusade?.” The English Historical Review 128, no. The English Historical Review 128, no. 534 (2013): 1047-1085.

Reeve, W. Paul, and Ardis E. Parshall, eds. Reeve, W. Paul, and Ardis E. Parshall, eds. Mormonism: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Pg. 103.

Rist, Rebecca, “Salvation and the Albigensian Crusade: Pope Innocent III and the plenary indulgence,” Reading Medieval Studies, pg. Reading Medieval Studies, pg. 95.

Rist, Rebecca. “Salvation and the Albigensian Crusade: Pope Innocent III and the plenary indulgence.” Reading Medieval Studies Reading Medieval Studies 36 (2010): 95-112.

“Statistics and Church Facts | Total Church Membership.” 2020. Newsroom.Churchofjesuschrist.Org. https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/facts-and-statistics.https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/facts-and-statistics. Accessed 3/7/20.

Shannon, Albert Clement. The Popes and Heresy in the Thirteenth Century. Villanova, Pennsylvania: Augustinian Press, 1949. Pg. 37.

Sibly, W.A.; Sibly, M.D. (2003). The Chronicle of William of Puylaurens: The Albigensian Crusade and Its Aftermath. Woodbridge, Suffolk, England, UK: The Boydell Press. pp. 127–128.

Simonis, Lorraine Marie Alice. “The Kingdom, the Power and the Glory: The Albigensian Crusade and the Subjugation of the Languedoc (thesis).” (2014). Pg. 14.

Smith, Thomas W. “How to craft a crusade call: Pope Innocent III and Quia maior (1213).” Historical Research 92, no. Historical Research 92, no. 255 (2019): 2-23. Pg. 6.

Spencer, Thomas M., ed. The Missouri Mormon Experience. University of Missouri Press, 2010. Pg. 50-51.

Stegner, Wallace Earle. The gathering of Zion: the story of the Mormon trail. University of Nebraska Press, 1964. Pg. vii.

Stephen C. LeSueur. The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1987. Pg. 247. Citing Affidavit of David Frampton, in Mormon Redress Petitions, 209-210.

Uebel, Michael. “Unthinking the Monster: Twelfth-Century Responses to Saracen Alterity,” Monster Theory: Reading Culture, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. (1996): 264-91.

Walker, Jeffrey N. “Mormon Land Rights in Caldwell and Daviess Counties and the Mormon Conflict of 1838: New Findings and New Understandings.” BYU Studies Quarterly 47, no. BYU Studies Quarterly 47, no. 1 (2008).

Winston, Kimberly. “Contested Sacred Space USA: Conflict And Cooperation In The Heartland – Religion News Service.” 2017. Religion News Service. https://religionnews.com/2017/08/11/contested-sacred-space-usa-conflict-and-cooperation-in-the-heartland/. Accessed 7 Mar 2020.

- Reeve, W. Paul, and Ardis E. Parshall, eds. Mormonism: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Pg. 103. ↑

- Clayton, William (1814-1879). “Come, Come Ye Saints.” Manchester Hymnal, English. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1840. 1912, 25th Edition (last known). 385 songs. The lyrics were written in 1846. ↑

- “Innocent III, Quia Maior, 1213.” As found in Bird, Jessalynn, Edward Peters, and James M. Powell, eds. Crusade and Christendom: Annotated Documents in Translation from Innocent III to the Fall of Acre, 1187-1291. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. Accessed March 7, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fh9x5. ↑

- Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia. “RESEARCH PROPOSAL: CRUSADE, LITURGY, IDEOLOGY, AND DEVOTION (1095-1400).” Neh.gov, Research Grant FB-56015-12. Pg. 1. ↑

- Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia. Invisible weapons: liturgy and the making of crusade ideology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017. ↑

- Moore, John, ed. Pope Innocent III and his world. Routledge, 2016. Ch. 22, pg. 1. ↑

- Power, Daniel. “Who went on the Albigensian Crusade?.” The English Historical Review 128, no. 534 (2013): 1047-1085. Pg. 1076. ↑

- Gaposchkin, Invisible Weapons, 203. ↑

- Shannon, Albert Clement. The Popes and Heresy in the Thirteenth Century. Villanova, Pennsylvania: Augustinian Press, 1949. Pg. 37. ↑

- Rist, Rebecca. “Salvation and the Albigensian Crusade: Pope Innocent III and the plenary indulgence.” Reading Medieval Studies 36 (2010): 95-112. ↑

- Ephesians 4:9, The Bible, New International Version (NIV). ↑

- Nickerson, Hoffman. The Inquisition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1923. Pg. 35. ↑

- “Innocent III, Quia Maior, 1213.” In Crusade and Christendom: Annotated Documents in Translation from Innocent III to the Fall of Acre, 1187-1291, edited by Bird Jessalynn, Peters Edward, and Powell James M., 107-12. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. ↑

- “Innocent III, Quia Maior, 1213,” in Crusade and Christendom, ed. Jessalyn et al. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Pope Innocent III, “Quia Maior,” Patrologia Latina, ed. Migne, vol. 216, col. 821. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Uebel, Michael. “Unthinking the Monster: Twelfth-Century Responses to Saracen Alterity,” Monster Theory: Reading Culture, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. (1996): 264-91. Pg. 268. ↑

- Baugh, Alexander L. “A call to arms: the 1838 Mormon defense of Northern Missouri.” PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1996. Pg. 26. ↑

- Bell, pg. 25. ↑

- Left: From Milton-Edwards, Beverley. “Jerusalem: Securing Spaces In Holy Places.” Brookings, 201.. https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/jerusalem-securing-spaces-in-holy-places/. Right: Winston, Kimberly. “Contested Sacred Space USA: Conflict And Cooperation In The Heartland – Religion News Service.” 2017. Religion News Service. https://religionnews.com/2017/08/11/contested-sacred-space-usa-conflict-and-cooperation-in-the-heartland/. Accessed 3/7/20. ↑

- The Doctrine and Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981. Section 57:1-2. ↑

- Smith, Joseph Fielding. Life of Joseph F. Smith. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1938. Pg. 340. ↑

- Howlett, David J. Kirtland temple: The biography of a shared Mormon sacred space. University of Illinois Press, 2014. ↑

- “Valley of God” in the Adamic language — Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Vol. 1, which cites Journal of Discourses 18:343 (Orson Pratt). ↑

- “Adam-Ondi-Ahman.” Emp.Byui.Edu, 2020. http://emp.byui.edu/SATTERFIELDB/PDF/Quotes/Adam-ondi-Ahman.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar 2020. ↑

- Winston, Kimberly. “Contested Sacred Space USA: Conflict And Cooperation In The Heartland – Religion News Service.” 2017. Religion News Service. https://religionnews.com/2017/08/11/contested-sacred-space-usa-conflict-and-cooperation-in-the-heartland/. Accessed 3/7/20. ↑

- Bell, Angela. “Trouble in Zion: the radicalization of Mormon theology, 1831-1839.” PhD diss., University of Missouri–Columbia, 2017. Pg. 9. ↑

- Gordon S. Wood, “Evangelical America and Early Mormonism,” New York History 61 (October 1980). Pg. 380. ↑

- Crawley, Peter, and Richard L. Anderson. “The Political and Social Realities of Zion’s Camp.” Brigham Young University Studies 14, no. 4 (1974): 406-420. ↑

- Daniel Ashby, James Keyte, and Sterling Price (Brunswick, Missouri), “Letter to Governor Lilburn W. Boggs” (Jefferson City, Missouri), September 1, 1838, in Mormon War Papers 1837-41, Missouri State Archives. ↑

- “Petition to Congress,” The Latter-day Saint’s Millennial Star, No. 28, vol XVII. Saturday, July 14, 1855. Reprinted from the History of Joseph Smith, a copy of the ‘petition to Congress for redress of our Missouri difficulties.’ ↑

- “Polygamy and Utah,” The Latter-day Saint’s Millennial Star, No. 8, vol XVII. Saturday, February 24, 1855. ↑

- Brown, Samuel Morris. In Heaven as It Is on Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death. Oxford University Press, 2011. Pg. 289. ↑

- Bird, Jessalynn, Edward Peters, and James M. Powell, eds. Crusade and Christendom: annotated documents in translation from Innocent III to the fall of Acre, 1187-1291. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. Pg. 454. ↑

- Crandall, Marilyn J. “The Little and Gardner Hymnal, 1844: A Study of Its Origin and Contribution to the LDS Musical Canon.” Byu Studies, vol. 44, no. 3, 2005, pp. 136–160. Pg. 138. ↑

- Bell, pg. 2. ↑

- Daviess County Circuit Court Records, C2690, p. 3. ↑

- Matthew 5:13, The Bible, King James Version (KJV). ↑

- Daviess County Circuit Court Records, C2690, p. 4 ↑

Frampton, T. Ward. “’Some Savage Tribe’: Race, Legal Violence, and the Mormon War of 1838.” Journal of Mormon History 40, no. 1 (2014): 175-207. Pg. 194. ↑

- The Doctrine and Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981. Section 52:42. ↑

- Bird, Jessalynn, Edward Peters, and James M. Powell, eds. Crusade and Christendom: annotated documents in translation from Innocent III to the fall of Acre, 1187-1291. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. Pg. 40. ↑

- Bird et al, pg. 5. ↑

- Frampton, pg. 195. ↑

- Largey, Zachary L. “The Rhetoric of Persecution: Mormon Crisis Rhetoric from 1838-1871.” (2006). Theses and Dissertations, Brigham Young University. Pg. 67. ↑

- “History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834],” p. 475, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed March 4, 2020. https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834/481. ↑

- Grua, David W., “Memoirs of the Persecuted: Persecution, Memory, and the West as a Mormon Refuge” (2008). Theses and Dissertations, Brigham Young University. Pg. 17. ↑

- Grua, pg. 17. ↑

- Grow, Matthew J.. “The Suffering Saints: Thomas L. Kane, Democratic Reform, and the Mormon Question in Antebellum America.” Journal of the Early Republic 29 (2009): 681 – 710. Pg. 682. ↑

- Cordon, Alfred. “Times and Seasons, 16 May 1842, vol 3, no 14” p. 793, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed March 4, 2020, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/times-and-seasons-16-may-1842/11 ↑

- Cordon, Alfred, “Times and Seasons,” p. 793, The Joseph Smith Papers. ↑

- Hicks, Michael. Mormonism and music: A history. Vol. 489. University of Illinois Press, 2003. Pg. 20, quoting Alexander Campbell. ↑

- Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay. The History of the Albigensian Crusade. Edited and translated by W. A. Sibly and M. D. Sibly. Woodbridge, UK: 1998. §226. Pg. 116. Continued quote: “…, those who recited the psalms more than those who attacked them, those who prayed more than those who sought to wound.” ↑

- O’Carroll, Michael. Veni Creator Spiritus: A Theological Encyclopedia of the Holy Spirit. Liturgical Press, 1990. Pg. 65. ↑

- Alexander, John Kimball. “Tarred and Feathered: Mormons, Memory, and Ritual Violence.” PhD diss., Department of History, University of Utah, 2012. Pg. 8. ↑

- Moore, Robert I. The formation of a persecuting society: authority and deviance in Western Europe 950-1250. John Wiley & Sons, 2008. Pg. ↑

- Cannon, Mark W. “The crusades against the Masons, Catholics, and Mormons: Separate waves of a common current.” Brigham Young University Studies 3, no. 2 (1961): 23-40. Pg. 23. ↑

- Cannon, pg. 26. ↑

- Cannon, pg. 36. ↑

- Hartley, William G. “Missouri’s 1838 Extermination Order and the Mormons’ Forced Removal to Illinois.” Mormon Historical Studies 2, no. 1 (2001): 5-27. Pg. 5. ↑

- Frampton, pg. 196. ↑

- Brandon G. Kinney. The Mormon War: Zion and the Missouri Extermination Order of 1838. Yardley, Penn.: Westholme Publishing, 2011. 236 pp. Notes, bibliography, index, photographs, maps. ↑

- Hartley, Pg. 5. ↑

- Frampton, pg. 197. ↑

- Sibly, W.A.; Sibly, M.D. (2003). The Chronicle of William of Puylaurens: The Albigensian Crusade and Its Aftermath. Woodbridge, Suffolk, England, UK: The Boydell Press. pp. 127–128. ↑

Leave a Reply